Student migration in the 19th century

‘The Reformed University of Ghent attracts attention in Belgium and abroad ... and

occupies an honourable position amongst European scientific institutions’, so proclaimed Rector Haus proudly during his speech at the opening the 1866 academic year. Ghent and Belgium do indeed have a leading position as a host university and country for the emerging international student migration.

Belgium has earned this leading position first and foremost through its industrial

reputation and highly developed engineering courses: almost all foreign students in the 19th century and during the interwar period who studied in Belgium did so at the Technical Schools of Ghent and Liege. Leuven and Brussels, which were only authorized to offer engineering courses much later on, initially proved to attract fewer foreign students. As a Catholic country with a progressive liberal constitution and political neutrality on the international stage, Belgium had the reputation of being quiet, cheap and modern. Moreover, the language of the well-structured educational system was French, which in the 19th century was the international language of culture.

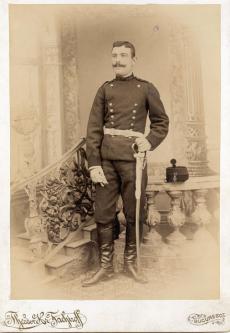

From the 1850s, Poles and Brazilians, Russians, Romanians, Greeks and Bulgarians

successively found their way to Ghent. In the second half of the 19th century, the foreign student body accounted for a quarter of the overall student population in Ghent. Relations were generally friendly: foreigners were members of sports clubs and student clubs. In 1872, a delegation of foreign students presented a banner to the Algemeen Gents Studentenkorps (General Body of Ghent Students) as a token of gratitude and sympathy. For the occasion, the university issued a special medal for the foreign students.

But reactions were mixed. In 1877, L'etudiant Catholique, the mouthpiece for the Catholic

students of Ghent, was not overly pleased with the presence of foreign students. The Latin Americans especially had a reputation for being charlatans who were seen mainly in parades and riots and less frequently at lectures – a premature judgment for which the magazine apologised in 1877, when only three Latin American students remained in Ghent. Their aversion was also related to the sympathy of international students for liberal ideas. The tug of war between liberals and Catholics over foreign students even took on a hint of necrophilia when, on their demise, there were negotiations as to who was allowed to arrange a funeral for the body.

Foreign students had an above average chance of dying in Ghent. The reason was

foreign diseases from which they had no immunity. But it was also symptomatic of the poor conditions in which they often lived. This is evidenced by the correspondence of their family with the Rector on financial difficulties, the need for a part-time job and the interruption of their studies. It also explained why some citizens of Ghent preferred not to rent quarters to foreign students.